As part of its commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and abolition of slavery in the United States, the Virginia Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Commission will construct the Emancipation Proclamation and Freedom Monument on Brown’s Island.

Donations can be made by check, payable to the Virginia Capitol Foundation, with a note indicating that the donation is for the Emancipation Proclamation and Freedom Monument. Checks can be mailed to:

Virginia Capitol Foundation

P.O. Box 396

Richmond, VA 23218

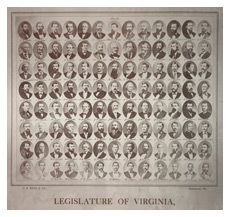

1887-1888 Members of the VA General Assembly. (Photo credit: Bells Mill Historical Research and Restoration Society, Inc., Chesapeake, VA.)

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 15 February 1868, and shows the 1867-1868 Virginia constitutional convention. Photo Courtesy of the Library of Virginia.

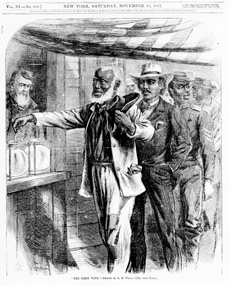

First Vote

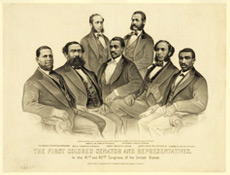

First African American Congressmen

Virginia African American State Legislators 1871-1872

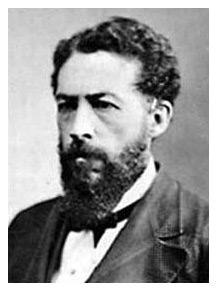

John Mercer Langston: First African American to represent

Virginia in the U.S. House of Representatives.

John

Mercer Langston Biography (SOURCE: Dinnella-Borrego, L., & the Dictionary

of Virginia Biography. John Mercer Langston (1829–1897). (2015, July 23).

In Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from this

link.)

The African American Legislators Database was created in 2004 by the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Commission as a part of the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. The database will eventually include all African American Legislators elected to the General Assembly during the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Commission ("MLK Commission") began the Virginia African American Legislators Project in the early 2000's and emphasized the Project during the Commonwealth's two-year commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. The Project is designed to create a database of all African Americans ever elected to serve in the Virginia General Assembly, from Reconstruction to the present. The Commission is appreciative of the generous assistance and extensive research conducted by former Secretary of Administration Viola Baskerville, the Library of Virginia, and Brenda Edwards, the Commission's legislative staff. Several resources were consulted, including A Register of the General Assembly of Virginia, 1776–1918, the Library of Virginia "Virginia Memory" database, and the groundbreaking research of Dr. Eric Foner, Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction (1996), and of Dr. Luther Porter Jackson, Negro Office-Holders in Virginia 1865–1895 (1945).

To celebrate the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 2013, the Commission determined that the Project should be launched with a roll call of the African American men who were elected to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868 and to the Virginia House of Delegates and the Senate of Virginia during Reconstruction from 1869 to 1890. African Americans elected to the Virginia General Assembly after Reconstruction and to the present day will be added to the database soon. Please check back for updates.

(choose one to learn more)

With the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, with the promulgation of the Virginia Consitiution of 1864 on April 7, 1864, and with the surrender of General Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865, marking the end of the American Civil War, tens of thousands of enslaved African men, women, and children were set free from the degradation of human slavery. In addition to the abolition of slavery, the end of the American Civil War resulted in life-altering changes and challenges in former slave states, including extending the right to vote to African American men.

After the American Civil War, during the era of Reconstruction between 1865 and 1877, as a condition of readmission into the Union, former slave states were required by Congress to create reconstructed governments, hold state conventions, and establish new constitutions; in Virginia, African American men were given the right to vote for and to be elected delegates to the convention, and 24 African American men were elected to the 1867–1868 Virginia Constitutional Convention, which created the Virginia Constitution of 1869.

The Virginia Constitution of 1869, the fifth of Virginia's seven state constitutions, was also known as the Underwood Constitution, named for Judge John C. Underwood, native New Yorker and federal judge in Virginia who served as the Convention's president. According to "Virginia Memory," a historical database of the Library of Virginia, "105,832 freedmen registered to vote in Virginia, and 93,145 voted in the election that began on October 22, 1867." Virginia Memory states that, during Reconstruction, "across the South about two thousand African Americans served in local and state government offices, including state legislatures and as members of Congress. About 100 African American men served in the General Assembly of Virginia between 1869 and 1890, and hundreds more in city and county government offices or as postal workers and in other federal jobs."

Across the South, legislation known as "Black Codes" was enacted to circumvent and thwart the newfound freedoms of former slaves; the reaction of Congress to these laws was the enactment of the Reconstruction Amendments to the United States Constitution, specifically the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects the rights of citizenship of freed men and women, and the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from denying citizens the right to vote due to race, color, or previous condition of servitude. After emancipation, these constitutional amendments laid the foundation by which many former enslaved Africans and their descendants were afforded equal rights as citizens under the United States Constitution, including the right to vote and run for elected public office.

Nearly a century would pass before the descendants of slaves would inherit and embrace the reality of the rights embodied in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments; however, the Reconstruction Amendments helped to transform the United States, according to President Abraham Lincoln, from a country that was "half slave and half free" to one in which the constitutionally guaranteed "blessings of liberty" would be extended to all the nation's citizens.

As a result of the resurgence of virulent racial discrimination that followed Reconstruction, Southern state governments enacted a system of laws known as "Jim Crow" laws, which established a rigidly segregated and legally sanctioned social system that subjugated and disenfranchised African Americans, again relegating them to second-class citizenship from 1877 until the mid-1960s.

During the era of Jim Crow, very few African Americans dared to brave the political and social realities of the time to run for public office or were able to register and vote under state constitutions and laws en force; from 1890 to 1968, African Americans were not represented in the Virginia General Assembly, the oldest continuous legislative body in the Western Hemisphere; in 1967, William Ferguson Reid, a Richmond doctor and community leader, became the first African American in the 20th Century elected to the Virginia House of Delegates.

William H. Andrews, born around 1839, may have been a schoolteacher in New Jersey before coming to Virginia. No evidence has come to light on his life prior to 22 October 1867, when he won a racially polarized election to represent Isle of Wight and Surry Counties in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. He also represented Surry in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871.

James D. Barrett was likely born a slave in Louisa County in 1833. He later moved to Fluvanna County, where he was a shoemaker, carpenter, and minister, Mr. Barrett represented Fluvanna in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. He labored for the welfare of African Americans. Mr. Barrett died in 1903 and is buried on the grounds of Thessalonia Baptist Church in Fluvanna, which he organized in 1868.

Thomas Bayne, also known as Samuel Nixon, a dentist and minister, was born a slave in North Carolina ca. 1824. After living in Norfolk, by 1855 he had escaped slavery and fled to Massachusetts. In 1860, he was elected to the New Bedford City Council, becoming one of only a handful of African Americans to hold office in the United States prior to Reconstruction. He was a member of the delegation of Virginia African Americans who met with President Andrew Johnson in February 1866 to press demands for civil and political rights; was one of the few African Americans to testify before the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction; was elected a vice president of the Union Republican State Convention in 1867; and was elected from Norfolk to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868, where he emerged as the most important African American leader and served on the Committee on the Executive Department of Government and the Committee on Rules and Regulations. He proposed legislation on school integration and equal citizenship and advanced the overhaul of the state's tax system. After Reconstruction, Thomas Bayne reduced his role in state partisan politics but remained active in local elections. He died in 1888.

James William D. Bland, a carpenter, a cooper, and U.S. tax assessor, was born in Prince Edward County in 1844. His father was a free man and a cooper who purchased his wife to ensure their children's freedom. He represented Prince Edward and Appomattox Counties in the Virginia Constitutional Convention and Charlotte and Prince Edward Counties in the Virginia Senate from 1869 to 1870, where he served on the Senate Committee for Courts of Justice. At the Virginia Constitutional Convention, Mr. Bland proposed a resolution requesting military authorities to direct railroad companies to allow convention delegates to occupy first-class accommodations, which many railroads had refused to do. He also introduced a measure guaranteeing the right of "every person to enter any college, seminary, or other public institution of learning, as students, upon equal terms with any other, regardless of race, color, or previous condition." He was considered to be the voice of compromise and impartiality in an age of turmoil and partisanship. James Bland was one of about 60 persons killed in 1870 when the third floor of the State Capitol collapsed.

William Breedlove, a blacksmith, was born free in Essex County about 1820. He represented Middlesex and Essex Counties in the Virginia Constitutional Convention, where he served on the Committee on Taxation and Finance. He was the leading spokesperson of his day in Essex County and served on the Tappahannock Town Council. He served postmaster there from 1870 until several months before his death in June 1871.

John Brown, was born a slave in Southampton County ca. 1830. In 1867, Mr. Brown, then illiterate, dictated a letter to a local Freedmen's Bureau agent, hoping to reestablish contact with his two daughters in Mississippi, who had been sold before the Civil War. He represented Southampton County in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868 and was a member of the Committee on the Judiciary. He voted regularly with the Radicals to reform and democratize the Constitution of Virginia to protect the rights of freed people. He died sometime after the census enumeration of his district on June 19, 1900.

David Canada, was born a slave, probably in Halifax County, and most likely worked as a stone mason. Little is known about him until October 22, 1867, when the county's voters elected him a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. More than 2,700 African Americans voted, while fewer than 1,000 whites cast ballots. He was the only black candidate to receive votes in every precinct, though he probably received no more than a few votes from whites. Mr. Canada campaigned for the new document's ratification in the face of intensifying interracial tension. He ran for a House of Delegate seat in 1869 but was defeated and disappeared from the historical record.

James B. Carter was born a slave of likely mixed race ancestry probably in Chesterfield around 1816. A bootmaker and shoemaker, James Carter represented Chesterfield and Powhatan Counties in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. He introduced a resolution at the convention directing the General Assembly to pass a law requiring students to attend school at least three months each year. Mr. Carter did not seek office after the convention. His funeral was held at African Baptist Church (later First Baptist Church, South Richmond) in Manchester in 1870.

Joseph Cox, was born in the mid-1830s in Powhatan County. Mr. Cox was a blacksmith who also worked as a bartender, tobacco factory worker, and day laborer, and he operated a small store. In 1867, he was president of the Union Aid Society, one of Richmond's largest African American organizations, and was a delegate to the state Republican convention. Mr. Cox represented Richmond in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. He was vice president of the Richmond chapter of the Colored National Labor Union in 1870, and two years later he helped lead the successful campaign to elect African Americans to the city council. He died in Manchester in 1880 and was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery, in the section of Chesterfield County that in 1914 became part of Richmond; a reported three thousand people marched in his funeral.

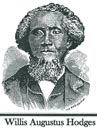

Willis A. Hodges was an antislavery activist, newspaper editor, and member of the Convention of 1867–1868. Born in Princess Anne County (later the city of Virginia Beach), he was the son of prosperous free African Americans. His younger brother Charles E. Hodges and nephew John Quincy Hodges both served in the House of Delegates. Before the Civil War, he moved between Virginia and Brooklyn, New York, where he preached, farmed, and helped establish a temperance society. In 1847 he cofounded an antislavery newspaper, the Ram's Horn, through which he befriended abolitionist John Brown. He wrote an autobiography and after the war returned to Virginia, where he opened a school and became involved in Republican Party politics. Mr. Hodges represented Princess Anne County in the constitutional convention and was the best known and one of the most active and vocal of the convention's twenty-four African American members, supporting radical reforms and racial equality. Later he served on the county board of supervisors and as the keeper of the Cape Henry lighthouse, perhaps the first African American to hold that position. Mr. Hodges died on September 24, 1890. (Photo credit: Bells Mill Historical Research and Restoration Society, Inc., Chesapeake, VA.)

Joseph R. Holmes was born into slavery circa 1838 in Charlotte County. He learned to read and write and became a shoemaker. After the Civil War, he supported reforms proposed by the radical wing of the Republican Party and was elected to represent Charlotte and Halifax Counties in the convention called to write a new state constitution. On almost every issue Mr. Holmes voted for the most radical reform proposals offered during the convention. In 1869 the son of his former owner reportedly threatened to kill Holmes for his political activities. Holmes sought an arrest warrant at the courthouse, but a scuffle broke out and he was shot and killed.

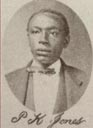

Peter K. Jones sat in the constitutional Convention of 1867–1868 and then served four terms in the House of Delegates. Born free in Petersburg about 1834, he first acquired property in 1857. Politically active after war, he urged African Americans to become self-sufficient and advocated for suffrage and unity. He moved to Greensville County about 1867, and that same year he won a seat at the convention called to write a new state constitution. A member of the convention's radical faction, Mr. Jones voted in favor of granting the vote to African American men and against segregating public schools. He represented Greensville County in the General Assembly from 1869 to 1877, working tirelessly to protect the rights of African Americans. Mr. Jones moved to Washington, D.C., and continued to support African American interests and the Republican Party. He died there in 1895.

Samuel F. Kelso was a member of the Convention of 1867–1868. Born into slavery, reportedly in Lynchburg, he emerged from the Civil War and abolition of slavery as a politically active educator. In 1867 he won election to the constitutional convention, representing Campbell County, and voted with radical reformers, including in opposition to the segregation of the newly created public schools. Appointed to a committee to invite General Ulysses S. Grant to visit the convention, Mr. Kelso was left behind by white members, who met with the general privately. He remained involved in Republican Party affairs but lost election to the House of Delegates in 1869. The following year Mr. Kelso taught at a one-room schoolhouse in Lynchburg and in 1871 worked for the post office. He died in 1880.

Lewis Lindsey, a musician and laborer, was born in Caroline County in 1833. After the war, he worked in the Tredegar ironworks, was a janitor at the Richmond custom house, and led a brass band. Mr. Lindsey was employed as a speaker by the Republican Congressional Committee in 1867 and was a delegate in that year to the Republican state convention from Richmond. He represented the city of Richmond in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868.

Peter George Morgan was born into slavery in Nottoway County in 1817. He worked as a shoemaker and purchased his freedom and that of his wife and children. After the Civil War he won election in 1867 to represent Petersburg in the convention called to write a new state constitution. A Republican he usually sided with the party's radical faction during the proceedings. After the convention Mr. Morgan represented Petersburg in the House of Delegates for a two-year term (1869–1871). He served three terms on the Petersburg city council. Committed to education, he was a trustee for Saint Paul Normal and Industrial School (later Saint Paul's College), founded by his son-in-law, James Solomon Russell. Mr. Morgan died at Russell's home in Lawrenceville in 1890.

Gallery of family documents »

William P. Moseley, a Republican from Goochland County, was a member of the Convention of 1867–1868 and of the Senate of Virginia from 1869–1871. Born into slavery, Mr. Moseley likely operated a boat on the James River before the Civil War. He was free by 1857, when he married the recently freed daughter of a nearby planter. After the war he lived in Richmond while buying land in Goochland and Fluvanna Counties and becoming involved in local and state politics. He held an important committee post at the Convention of 1867–1868 and voted for all of the new constitution's most important reforms. In 1869 he easily defeated the white Conservative Party candidate for a seat in the Senate of Virginia, where he offered an unsuccessful bill to prohibit racial segregation in the state's new public schools. After serving one term, Mr. Moseley remained active in party politics but did not run again for public office. He farmed, owned land in several counties, and acquired a brick house in Richmond. Mr. Moseley died in 1890.

Frank Moss was the only African American to be a member of the Convention of 1867–1868, the Senate of Virginia, and the House of Delegates. Little is known about his early life, but he was born likely in Buckingham County in the mid-1820s. Local tradition holds that he was born into a free family, but evidence also exists that he was enslaved. In 1867 Mr. Moss won election to represent Buckingham in the convention called to write a new state constitution. He supported radical reformers on all major issues, but his speeches were considered divisive. He represented Appomattox and Buckingham Counties in the Senate of Virginia from 1869 to 1871, and voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. In November 1873 Mr. Moss won election to represent Buckingham County for one term in the House of Delegates. He died in 1884, but public records do not contain the date or circumstances of his death.

Edward Nelson was a member of the Convention of 1867–1868. Probably born into slavery in Charlotte County, he emerged from the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery as prominent among African Americans in the county. In 1867 he won election to the constitutional convention and voted with the radical reformers, except when it came to their attempt to prohibit segregation in the new public school system. He largely disappeared from the historical record, attending a convention in Washington, D.C., and testifying about the violent death of another black politician, Joseph R. Holmes. Mr. Nelson's date of death is unknown.

Daniel M. Norton, a physician, served in the Senate of Virginia for twelve years. Born into slavery early in the 1840s, he escaped to New York in the mid-1850s with his brother Robert. He learned the medical profession and moved to Yorktown by 1865, quickly becoming a leader among the area's freedpeople. The region's voters elected him to the state Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868 and he later served in the Senate of Virginia from 1871 to 1873 and from 1877 to 1887. His brothers Robert and Frederick Norton became members of the House of Delegates. Daniel Norton often clashed with the Republican Party's leadership and launched unsuccessful candidacies for the House of Representatives. He aligned with the Readjuster Party in its early stages and played a key role in bringing African American voters into the short-lived, but powerful faction. He later clashed with political leader William Mahone, who engineered his removal from the Senate of Virginia. Mr. Norton owned considerable property in Yorktown, including the historic customs house. He died in 1918.

John Robinson was a member of both the Convention of 1867–1868 and of the Senate of Virginia. Born free in Cumberland County in 1825 he achieved some measure of prosperity before the Civil War, but he moved to Amelia County in 1864 after mobs attacked him twice. Highly litigious, he became involved in at least ten lawsuits to safeguard his property. Likely related to James F. Lipscomb, who sat in the House of Delegates, Robinson was elected to represent Cumberland County in the convention called to write a new state constitution. In 1869 he won a seat to the Senate of Virginia, representing Amelia, Cumberland, and Nottoway Counties. He lost reelection in 1873 and later in life operated a tavern called Effingham House, where he died in 1908.

Born to free parents in 1840, James Thomas Sammons Taylor served with the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War and wrote letters to the New York Anglo-African during his service. Described as a radical, he won election in 1867 to represent Albemarle County in the constitution called to write a new state constitution. African Americans, voting for the first time in Virginia, overwhelmingly supported him. Mr. Taylor spoke occasionally during convention and voted with the majority to approve the new constitution, which provided for universal manhood suffrage and the establishment of a statewide public school system. In subsequent years he twice ran for a seat in the House of Delegates, but he lost both times. Mr. Taylor remained a prominent member of Charlottesville's African American community well into the twentieth century. He died of pneumonia in 1918.

George Teamoh, born a slave in Portsmouth in 1818, was a ship's carpenter, caulker, and tailor, among other jobs. He was a delegate to the Virginia Black Convention of 1865 and a Union League organizer. He served in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868 from Norfolk County and Portsmouth. He wrote that "agricultural degrees and brickyard diplomas" were poor preparation for the complex proceedings. However, he did support the disenfranchisement of former Confederates. Mr. Teamoh served in the Senate of Virginia from Norfolk County and Portsmouth from 1869 to 1871, and, as a member of the Senate, he supported the formation of a biracial labor union at the U.S. Navy yard in Norfolk. Later, he was denied re-nomination to the Senate of Virginia in 1871, because of party factionalism, and ran unsuccessfully for the Virginia House of Delegates. He was a strong advocate of African American education. He wrote autobiographical notes that were published in 1990 under the title, God Made Man; Man Made the Slave: The Autobiography of George Teamoh.

Most likely born into slavery circa 1822, Burwell Toler became an ordained minister in 1865 and founded churches in at least four counties. In 1867 he won election to represent Hanover and Henrico Counties in the convention called to write a new state constitution. Mr. Toler served on the prestigious Committee of Thirteen, which established procedures for the convention, and generally sided with the Republican Party's radical faction. His quest for a seat in the House of Delegates in 1868 was stopped when that year's elections were cancelled, and he lost his bid in the following year's contest. Mr. Toler remained a prominent minister and ten years later served as the moderator for the newly created Mattaponi Baptist Association of Virginia. He died in 1880.

John Watson was a member of the Convention of 1867–1868 and of the House of Delegates from 1869 to 1870. Born into slavery, he was owned at the time of Civil War by a lawyer in Mecklenburg County and worked as a shoemaker after the war. He served as a trustee for a Freedmen's School and in 1867 won election to the constitutional convention, where he voted with the radical reformers and introduced three resolutions himself. After the killing of an African American politician in Charlotte County, Mr. Watson and several others spoke up and were arrested for inciting violence; the charges were later dropped. In 1869 he was elected to the House of Delegates as a Republican from Mecklenburg County and voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Mr. Watson died while in office.

William H. Andrews, born around 1839, may have been a schoolteacher in New Jersey before coming to Virginia. No evidence has come to light on his life prior to 22 October 1867, when he won a racially polarized election to represent Isle of Wight and Surry Counties in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. He also represented Surry in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871.

William Horace Ash, born in slavery in 1859 in Loudoun County to William H. and Martha A. Ash, preferred to call himself Horace Ash of Leesburg. He was educated at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) and graduated in 1882. He relocated to Nottoway County, where he taught at a school for African American girls. He served as a county delegate to the Republican state party convention in 1884; three years later, he was nominated for the Virginia House of Delegates for the district comprising Amelia and Nottoway Counties. He served in the House of Delegates from 1887 to 1888 and was a member of the standing Committees on Propositions and Grievances and on Printing. He studied law and identified himself as a lawyer, but he is not known to have practiced law; he remained concerned with education. He also taught agriculture at Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute, later named Virginia State University. Mr. Ash died in 1908.

Born into slavery in 1863, Britton Baskervill acquired an education after the Civil War and taught school as one of his occupations. In 1887 Republican Party leader William Mahone engineered his nomination as the party's candidate to the House of Delegates. The African American majority among the Mecklenburg County's electorate provided Mr. Baskervill an easy victory over his Democratic opponent in the general election. He stood by Mahone in 1888 when most African Americans supported the independent congressional candidacy of John Mercer Langston. A year later, however, Mr. Baskervill lost Mahone's political support and with it the Republican Party's nomination for the seat in 1889. He returned to teaching and farming, never again holding public office, before dying of tuberculosis in 1892.

Edward David Bland was born a slave probably in Dinwiddie County in 1848. Mr. Bland, the son of Frederick Bland, a shoemaker and minister, came to Petersburg following the American Civil War and attended night school. About 1874 he moved to City Point, in Prince George County, where he worked as a shoemaker. Mr. Bland represented Prince George and Surry Counties in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1879 to 1884, where he served three terms and was a member of the House Committees on Executive Expenditures, on Schools and Colleges, on Agriculture and Mining, on Claims, Retrenchment and Economy, on Propositions and Grievances, on Enrolled Bills, and on Officers and Offices at the Capitol. Mr. Bland died in 1927 and is interred at the People's Memorial Cemetery in Petersburg.

Phillip S. Bolling, a farmer and brick mason, was born a slave in Buckingham County around 1849 to Samuel P. and Ellen Munford Bolling. His father owned land in Farmville and Lynchburg, and Phillip Bolling acquired the Lynchburg property from his father in 1872. He worked for his father's brickyard in Farmville, and they were both listed as brick masons in the 1880 census. He became very interested in politics and ran for the Virginia House of Delegates as a Readjuster in 1883. On election day, Democrats charged that Mr. Bolling was a Prince Edward resident and ineligible to represent Buckingham and Cumberland Counties. Voters ignored the warnings. Winning the election by 538 votes and certified by the local board of elections to represent Buckingham and Cumberland Counties in the Virginia House of Delegates, he was appointed to the House Committees on Banks, Currency, and Commerce; on Officers and Offices at the Capitol; and on Rules. The Democrats again challenged his election, when the Democratic majority of the Committee of Privileges and Elections rejected evidence that Bolling had been registered to vote in Cumberland County, had voted there from 1881 to 1883, and had served as a juror there as recently as June 1883. Because he had been working at a brick kiln in Prince Edward County before the election, the committee ruled that he was not a resident of Cumberland and was ineligible to represent the district in the House of Delegates. He was later elected to the Prince Edward County Board of Supervisors. Because their names were similar and some documents confused he and his father, who served in the House of Delegates from 1885 to 1887, the election of Phillip Bolling to the House of Delegates and his brief service there have not been included in references on African Americans in Virginia politics late in the nineteenth century. He died on April 18, 1892, in Petersburg.

Samuel P. Bolling, a farmer, brick mason, and brick manufacturer, and the son of Olive Bolling, was born into slavery in Cumberland County in 1819. He was trained as a skilled mechanic, and likely purchased his freedom shortly before the American Civil War. After the war he also purchased land and started a brickyard, which employed many individuals who helped construct many of the brick buildings in Farmville and the surrounding countryside. He eventually amassed more than 1,000 acres in Cumberland County. He agreed with those in the General Assembly who proposed to scale down the principal and interest to be paid on the antebellum debt in order to pay for new public schools and other public projects. Mr. Bolling served in the Virginia House of Delegates, representing Cumberland and Buckingham Counties, from 1885 to 1887, a seat his son previously held. He was a member of the following House Committees: Claims; Manufactures and Mechanical Arts; and Retrenchment and Economy. He was active in the Mount Nebo Baptist Church in Buckingham County as a deacon, trustee, and treasurer. Mr. Bolling died in 1900.

Tazewell Branch was a shoemaker, storekeeper, and assistant assessor of internal revenue. The son of Richard Branch and Mary Hays, Mr. Branch was born a slave in 1828 near the town of Farmville in Prince Edward County and served as a house servant. He learned to read and write as well as the skill of shoemaking during slavery. In 1868 and 1869 he was one of the trustees who purchased land for what was to become Beulah African Methodist Episcopal Church. By 1873 he owned property in Farmville and sat on the town council. His children included Clement Tazewell Branch, who received his M.D. from Howard University in 1900 and settled in Camden, New Jersey, to become the first African American to serve on the city's school board, and Mary Elizabeth Branch, who attended Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, now Virginia State University, and taught there for twenty years. Branch Hall is named in her honor. In 1930, she became president of Tillotson College in Austin, Texas. Tazewell Branch was said to have refused pay for service in party campaigns and quit politics when he observed politicians becoming corrupt. He represented Prince Edward County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1874 to 1877. He died in New Jersey on April 30, 1925, and was buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Farmville.

William Henry Brisby was born free in New Kent County in 1836 to Roger Lewis, an African American, and Marinda Brisby, who was of Pamunkey Indian origins. Prior to the Civil War he established himself as a blacksmith. He worked on the construction of the Richmond and York River Railroad. He later testified that the slave regime's withholding of education made him a Unionist, and as late as 1860 he signed with his mark. By 1863, however, he could sign his name and later obtained books related to the law. Mr. Brisby represented New Kent County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871, serving on the Officers and Offices at the Capitol Committee. A landowner, he later served on the New Kent Board of Supervisors from 1871 to at least 1881 and was a justice of the peace from 1870 until 1910. A fisherman as well, Mr. Brisby helped slaves and escaped Union prisoners of war slip out of Richmond during the American Civil War, stowing them away in his cargo transports. Mr. Brisby died in 1916.

Goodman Brown was born free in Surry County in 1840, a member of three generations of free men. His father was a landowner and at the age of 22 Goodman Brown enlisted in the U.S. Navy as a cabin boy aboard the USS Maratanza during the American Civil War. He was discharged December 20, 1864. A farmer, he attended night school and was later instructed by his wife, one of the first African American school teachers in Surry County. He represented Prince George and Surry Counties in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1887 to 1888, where he served on the House Immigration and the Retrenchment and Economy Committees. He died July 4, 1929, in Surry County and is buried near Bacon's Castle.

the son of Jacob and Peggie Carter, was born in 1845 in the town of Eastville in Northampton County. He worked as a house servant while in slavery; however, he ran away during the American Civil War and enlisted on October 30, 1863, in Company B of the 10th Regiment United States Colored Infantry. He mustered out on May 17, 1866. After the war, Carter was educated at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, now Hampton University. He became an important figure in Republican politics on Virginia's Eastern Shore and served in the Virginia House of Delegates from Northampton County from 1871 to 1879, one of the longest tenures among the 19th century African American members of the General Assembly. He introduced measures concerning taxes on oysters, the boundaries of election precincts, correcting prisoner abuse, improving the care of black deaf-mutes, and providing housing for the elderly and poor in Richmond. A large landowner, he also introduced bills to combat the exclusion of African Americans from jury service and to improve the treatment of prisoners and abolish the whipping post as a punishment for crime. He was in the delegation from the General Assembly that met with President Ulysses S. Grant to support what became the Civil Rights Act of 1875. He served on the following House Committees: Agriculture and Mining, Retrenchment and Economy, Claims, and Militia and Police. Later, Mr. Carter was a doorkeeper of the Senate of Virginia from 1881 to 1882. He was appointed by the General Assembly to the Board of Visitors of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, now Virginia State University. His son studied medicine at Howard University and became a physician at the veterans' hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama. Peter Jacob Carter died in 1886.

Matt Clark, a farmer, was born a slave in 1844 to Mathew and Chaney Clarke. He became a landowner in Halifax County. In the General Assembly, he often signed his name simply "Matt Clark," without the "e." He represented Halifax County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1874 to 1875 and served on the House Committee on Asylums and Prisons. He introduced a resolution supporting the improvement of living conditions at the Central Lunatic Asylum, now Central State Hospital, in Petersburg and agreed to the refinancing of the state war debt at a lower interest rate or repudiating a portion of the debt and using the remaining revenue to support the new public school system and other public programs.

George William Cole, a teacher and farmer, was born free in Athens, Georgia, in the late 1840s to William and Martha Cole. Inspired by his parents and perhaps by Emancipation and Reconstruction, he developed a desire for education and self-improvement. He entered Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, now Hampton University, in 1872. By 1879, Mr. Cole had made his way to Essex County, married Edith Banks, and emerged as the Republican candidate for the county seat in the Virginia House of Delegates. He won election to the House seat to represent Essex County from 1879 to 1880. After the session began on December 3, 1879, Mr. Cole joined 15 other Republicans, of whom 10 were African Americans, to form a wedge between a nearly equal number of Funders and Readjusters that resulted in a new slate of House leaders, among them a few African American office holders, to replace Confederate veterans in insignificant functions. Mr. Cole served as a member of the House Committee on Labor and the Poor. During his tenure, he did not introduce any major legislation; however, he supported a measure that would lower taxes on malt liquor, spirits, and wine vendors and supported the constitutional amendment to repeal the poll tax. Little is known about Mr. Cole after his term in the Virginia General Assembly. The date of his death is unknown.

Asa Coleman was born a slave probably in North Carolina in the early 1830s. His parents may have been Matthew and Frances Coleman. He moved to Halifax County by 1869. Before the American Civil War, he may have lived in Louisiana. He had a limited education, but he was well versed in politics. In 1872 Mr. Coleman bought at public auction 150 acres of land, for which he paid $982.50. The county approved the deed and conveyed it to him three years later. He represented Halifax County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1871 to 1873, serving three sessions. He was a member of the House Committee on Asylums and Prisons and was with the General Assembly delegation that met with President Ulysses S. Grant in 1872 to support what became the Civil Rights Act of 1875. A farmer and carpenter, Mr. Coleman is believed to have died sometime after February 24, 1893.

Johnson Collins, a native of Virginia, was born probably into slavery in August 1847. In 1870, he lived with his family in Brunswick County and earned his living as a laborer. In November 1879, he won a three-way race for a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, representing Brunswick County from 1879 to 1880. He served as a member of the House Committees on Federal Relations and Resolutions and on Public Property. He supported legislation to eliminate the poll tax, reduce the tax on malt, liquor, spirits, and wine vendors, and reduce the principal of the public debt and refinance the interest. After his service in the Virginia General Assembly, Mr. Collins relocated to Washington, D.C., with his family, where he worked as a watchman for about 20 years. Mr. Collins died on November 3, 1906, and is buried in Columbian Harmony Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Aaron Commodore was born in 1819 or 1820 as a slave probably in Essex County. A shoemaker, he purchased a home and land in Tappahannock before he became a member of the General Assembly. He was an influential community leader and represented Essex County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1875 to 1877, where he served on the House Militia and Police Committee. He was a member of First Baptist Church, Tappahannock. Mr. Commodore died in June 1892.

Miles Connor was a farmer and minister born a slave probably in Norfolk County in the early 1830s to parents Richard and Matilda Connor. He served as a valet and house servant. He was educated and could read and write. After emancipation, Mr. Connor emerged as a leader among the freedmen of Norfolk County, assisting in the organizing of churches and fraternal societies. He represented Norfolk County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1875 to 1877, serving on the House Militia and Police Committee. After leaving the General Assembly, he served as a justice of the peace from 1887 to 1891 in Norfolk County. His son Miles Washington Connor became the first president of Coppin State Teachers College (later Coppin State University) in Baltimore, Maryland. Miles Connor died in June 1893 and his funeral was held at Churchland Grove Baptist Church.

Henry Cox was born in Powhatan County in 1832, though it is unclear if he was enslaved or free. A shoemaker, he became a landowner early, purchasing 37 acres in 1871. He represented Chesterfield and Powhatan Counties in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871 and Powhatan County from 1871 to 1877, serving on the Committees on Officers and Offices at the Capitol, on Labor and the Poor, and on Militia and Police. Mr. Cox was with the delegation that in 1872 met with President Ulysses S. Grant to get his support for what became the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Mr. Cox died sometime after 1910, when he is listed in a Washington, D.C. city directory.

Isaac Dabbs, a laborer, was born a slave probably late in the 1840s in Charlotte County to George and Frankie Dabbs. In the 1870 census he was reported as not being able to read nor write. A Radical Republican, he represented Charlotte County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1875 to 1877. He died after the census enumeration of his ward in April 1910.

Born to free parents about 1844, McDowell Delaney worked for a Confederate infantry company during the Civil War and likely held a job later with the Freedmen's Bureau. He entered politics by 1869 when he lost a race for the county's House of Delegates seat. Two years later he won election by a large margin to represent Amelia County in the House of Delegates. There he sided with the majority in trying to circumvent the Funding Act of 1871. Divisions within the local Republican Party likely caused his failed reelection bid, though he did represent Amelia at a state convention of African Americans in 1875. In subsequent years Mr. Delaney served in a variety of local offices, including justice of the peace, coroner, and constable. He also became engaged in such occupations as teacher, Baptist minister, and farmer. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1926.

Amos A. Dodson was born a slave in Mecklenburg County in 1856. He worked as a farmer, deputy collector with the Internal Revenue Service, and teacher. The son of a blacksmith, Mr. Dodson attended school. He was a born orator and was active in politics. He represented Mecklenburg County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1883 to 1884. He moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he became a partner in an undertaking business and through this owned a coffin manufactory. He died there in 1888.

Jesse Dungey was born free about 1820 and became a skilled laborer. By 1847 he began acquiring land, eventually owning 248 acres at the time of his death. The Freedmen's Bureau recognized him as a community leader after the Civil War, noting his work in building a school and church for African Americans. In 1871 Mr. Dungey was elected as a Republican to represent King William County in the House of Delegates. He sided with the Readjusters in debates and votes over how to settle Virginia crippling pre-war debt. After his term in office he served as a minister and census enumerator for the county. Mr. Dungey died in 1884.

Born into slavery in 1831, Shed Dungee worked as a cobbler and later became a licensed preacher. Elected to represent Buckingham and Cumberland Counties for two terms in the House of Delegates, he took his seat in 1879, thirty-two years after he reportedly accompanied his owner for a term in the General Assembly. Mr. Dungee introduced an unsuccessful bill to end the restriction on interracial marriage, on the grounds that outlawing such intermarriage violated the United States Constitution. After winning reelection in 1881 he did not seek office in 1883, though he remained active in the Readjuster and Republican Parties during the 1890s. Mr. Dungee died in 1900.

Isaac Edmundson was born into slavery about 1840 and during the Civil War he served as his owner's body servant. In 1869 he won a seat to represent Halifax County in the House of Delegates. After his two-year term ended he worked as a barber and was able to secure both credit and real estate. He also held good enough political connections that the General Assembly passed a bill releasing him from a fine he owed to the Halifax County court. In 1924 Mr. Edmonson successfully applied for a state pension under a law that compensated African Americans who served the Confederate military in non-combat roles during the Civil War. He died in 1927.

Ballard Trent Edwards, a bricklayer, plasterer, and contractor, was born free in Manchester (now part of Richmond) in 1828 of mixed-race ancestry. His mother was a teacher, and he opened a school for freedmen in Manchester after the American Civil War. He held office as overseer of the poor in Chesterfield County, and as a magistrate after Manchester became a city in 1874. He represented Chesterfield and Powhatan Counties in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871, where he proposed a measure banning racial discrimination by railroad and steamboat companies. A leader in the First Baptist Church, Manchester (later First Baptist Church of South Richmond), Mr. Edwards was also active in the Masons. He died in 1881.

Joseph P. Evans was born a slave in 1835 in Dinwiddie County and purchased his freedom in 1859. During Reconstruction, he was a prominent leader of Petersburg's African American community, serving as a delegate to the Republican state convention of 1867, and in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1871 to 1873, representing Petersburg. Mr. Evans also represented Petersburg in the Senate of Virginia from 1874 to 1875. While a member of the General Assembly, Mr. Evans backed legislation to require compulsory education and guarantee African Americans the right to serve on grand juries when one of the litigants was an African American. He also held positions as a letter carrier and as an inspector at the Petersburg customhouse. He was elected president of a black labor convention in Richmond in 1875, where he urged African Americans to organize themselves independently in politics and as workers. He ran unsuccessfully as an independent candidate for Congress in 1884. His son, William W. Evans, represented Petersburg in the General Assembly from 1887 to 1888. Joseph P. Evans died in 1889.

William Dennis Evans was born free in Prince Edward County in 1831 and part of an extended family who had been landowners since before 1800. Mr. Evans learned the trade of painting and paperhanging as an apprentice to a master before the American Civil War. He attended a night school taught by northern missionaries and later became interested in politics. Mr. Evans purchased property in Farmville, was a trustee for the First Baptist Church, and sat on the town council. He received contracts for the interior decoration of buildings in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere. William D. Evans represented Prince Edward County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1877 to 1880. He died in 1900.

William W. Evans was born a slave ca. 1860 in Dinwiddie County. The son of Joseph P. and Josephine Evans, William Evans attended school in Petersburg and worked as a letter carrier and possibly a barber early in his career. By 1887 he had become editor of a Republican newspaper that advocated improvements in the political and material lives of African Americans. He obtained a law license in 1888. He represented Petersburg in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1887 to 1888. He died in 1892.

William Faulcon was born in 1841 in Surry County, probably into slavery and likely of mixed-race ancestry. After the Civil War he operated a blacksmith's shop. He began purchasing land in the county in 1879, eventually acquiring ninety acres. Little is known about how he became involved in politics, but local Republicans nominated him for the House of Delegates in 1885. Mr. Faulcon won the seat handily representing Surry and Prince George Counties, but he did not present legislation or speak on the record during the term's first session. He submitted a few bills on behalf of Surry County residents during the extra session. Mr. Faulcon was the Republican nominee for the seat in 1891, but he withdrew from the race before election day. He died on an unknown date probably not long before April 9, 1904, when the Surry County Court ordered the appraisal of his estate.

George Fayerman, a storekeeper, was born free about 1830 to George and Phoebe Fayerman. His father may have fled from Haiti to Louisiana during the slave insurrection led by Touissant l'Overture. Though he claimed Louisiana as his birthplace and probably had Haitian ancestry, evidence suggests he may have been born in Jamaica. Mr. Fayerman was literate in both French and English. After the American Civil War, he came to Petersburg where he established a grocery store, helped organize the Republican Party in the city, and attended the state Republican convention in 1868. Mr. Fayerman served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871, where he sponsored civil rights legislation. He served as a member of the Petersburg City Council from 1874 to 1875. He died in 1890.

James Apostle Fields was born a slave in Hanover County in 1844. He was the son of a shoemaker and became a teacher and lawyer. As a young man, he served as caretaker of the horses used by lawyers attending court at the Hanover Court House, and he spent considerable time in court observing the proceedings, which very likely inspired him to become a lawyer and a commonwealth's attorney. Mr. Fields became a refugee during the American Civil War. He graduated from Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, now Hampton University, in 1871 as a member of the institution's first graduating class. He also attended Howard University, graduating in 1882 with a law degree. Mr. Fields taught school before and after law school, and was later elected doorkeeper of the Virginia House of Delegates for the 1879–1880 session. He was eminently successful as a lawyer. Mr. Fields represented Elizabeth City, James City, Warwick, and York Counties and the city of Williamsburg in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1889 to 1890. He died in 1903.

Alexander Quincy Franklin was born in Richmond in 1852 to a former slave who had freed himself and possibly a white mother who taught him to read and write. He became a schoolteacher in Charles City County and helped establish Bull Field Academy, a school for African Americans. He also served as the county's commissioner of revenue for many years. In 1889 Mr. Franklin won election to represent the county in the House of Delegates for one term. One of only three African Americans elected in 1889 they were the last black candidates to win election to the General Assembly until 1967. Mr. Franklin died in 1924.

John Freeman represented Halifax County in the House of Delegates from 1871 to 1873. One of several African American men of that name in the city of Richmond, where he was born, and Halifax County, where he moved in 1870 and bought property in 1872, it is not known how he emerged as a political leader among African Americans. He represented Halifax County in the Republican Party state conventions of 1870 and 1873 and was active on the floor during the two sessions of the General Assembly in which he served. He sought to, among other things, authorize local referenda on the state’s fence law, repeal the Funding Act of 1871, investigate the conditions under which elections were held, and abolish corporal punishment at the whipping post. He was also a member of the Republican Party’s State Central Committee. Freeman did not seek reelection in 1873. He died in 1876.

William Gilliam served in the House of Delegates from 1871 to 1875. He represented Prince George County, where he was born to a free African American couple. Gilliam was a farmer who owned a four-acre tract of land on the outskirts of Petersburg; he was elected to the first of two consecutive terms in the House of Delegates in 1871. Identified in newspaper reports as a Radical Republican, Gilliam was active in the assembly and introduced numerous bills, although only one—authorizing a Prince George County business to construct a pier on the James River—passed. When he ran for a third term in 1875, some ballots in his district were lost and others were not reported; his Conservative opponent was declared the winner and seated despite Gilliam’s request for a recount. After this, Gilliam appeared to withdraw from partisan politics. He moved with his family to New York City, where he died in 1893.

James P. Goodwyn represented Petersburg in the House of Delegates from 1874 to 1875. Born in the 1830s, reportedly in Petersburg and probably into slavery, Goodwyn was elected as a Republican in 1873 and appointed to a seat on the important Committee on Privileges and Elections. During his tenure he sought, among other things, to invite ministers of Richmond churches, regardless of color, to open the house with prayer; to refer to the Committee on Propositions and Grievances the section covering African Americans in the superintendent of public instruction’s annual report; to reintroduce the popular election of judges; and to incorporate the Masonic Temple Association of the City of Petersburg. These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful save the last. He also opposed, unsuccessfully, the erection of a statue of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in Richmond’s Capitol Square. Goodwyn did not seek or was not nominated for reelection. Sometime after 1883 he moved with his family to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where he worked as a porter until 1910. The date and place of his death are not known.

Armistead Green was born enslaved and gained freedom at the end of the Civil War. He rose from tobacco factory worker to grocery store owner and co-owner of a mortuary. He also invested in a brick-manufacturing facility. In 1881 he won the first of two terms in the House of Delegates representing Petersburg. A member of the Readjuster Party, he generated nationwide newspaper coverage when he criticized fellow party member and congressman John S. Wise for saying he would only meet African American members of the General Assembly in the backyard rather than in the parlor. Mr. Green served as interim treasurer for the board of visitors of the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (later Virginia State University). He continued his business ventures until his death of Bright's disease in 1892.

Robert Gilbert Griffin, member of the House of Delegates (1883–1885), was born in 1847 in Yorktown, the son of an enslaved woman and a prosperous white man. Griffin’s father acknowledged Griffin as his son and made arrangements in his will to free him and his family. When his father died in 1859 his estranged white family blocked these provisions. Griffin spent much of his adult life attempting unsuccessfully to claim his inheritance. In the early 1860s he moved to Philadelphia where he enlisted in the United States Colored Troops. He married in 1871 and returned to Yorktown where he became involved in politics. His Republican Party work earned him appointment as the town’s postmaster. In 1883 Griffin won election to a two-year term in the House of Delegates representing the district that included the counties of York, Warwick, James City, and Elizabeth City and the city of Williamsburg. After his political service ended and an unsuccessful run for sheriff, Griffin bought and sold property, harvested oysters, and farmed. He died Washington, D.C., in 1927 and was buried in Collingdale, Pennsylvania

Nathaniel M. Griggs was a member of the House of Delegates from 1883 to 1884 and of the Senate of Virginia from 1887 to 1890. Born into slavery in Farmville in the mid-1850s, he learned to read and write. After the Civil War he lost a factory job, reportedly for making political speeches. He defeated a white Readjuster candidate to win election as a Republican to represent Prince Edward County in the House of Delegates. After serving a single term, Mr. Griggs won election to the Senate of Virginia in 1887, this time as a Readjuster defeating a Republican. Representing Amelia, Cumberland, and Prince Edward Counties, he supported the funding of public schools and opposed measures designed to prevent African Americans from voting. He served one term before moving to Washington, D.C., where he worked for the Bureau of Printing and Engraving. After living for a time in Philadelphia, Mr. Griggs returned to Farmville, where he died on July 5, 1919.

Ross Hamilton was born into slavery in Mecklenburg County and served as a member of the House of Delegates (1870–1883). Hamilton had the longest legislative career of any African American in nineteenth-century Virginia one of the best-known African American legislators in Virginia. Hamilton was first elected to the House of Delegates in a special election on May 26, 1870, and took his seat on June 2, 1870. In 1877 the Speaker appointed Hamilton to the important Committee on Privileges and Elections as the least-senior member. He also served on the Committees on Claims, on Retrenchment and Economy, on Immigration, and on Labor and the Poor. Hamilton regularly attended county, district, and state Republican Party conventions, was a member of the Committees on Resolutions and on Finance at the state convention in August 1875, and was a delegate to Republican national conventions in 1872 and 1876. In 1883, Hamilton lost the party nomination for an eighth term in the House of Delegates. In November 1889, Hamilton won election again to the House of Delegates to represent Mecklenburg County by defeating a white man, which was the last nineteenth-century general election in which any African American won election to the General Assembly. On January 3, 1890, less than a month after the session began, the House declared Hamilton’s election improper and seated his opponent. Ross Hamilton died at his residence in Washington, D.C., on May 2, 1901, and was buried on the grounds of Boydton Institute in Boydton.

Alfred William Harris was born enslaved in 1853 in Fairfax County. Little is known about his early life, but during the Civil War his family moved to Alexandria where he attended a school operated by the Freedmen's Bureau. He won a seat on the Alexandria common council as a 20-year-old and became a lawyer. Mr. Harris relocated in Petersburg and in 1881 won the first of four consecutive terms term in the House of Delegates representing Dinwiddie County. He is best known for introducing the bill that chartered Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (later Virginia State University) in the House of Delegates. He played key roles during the college's first years, serving as its de facto treasurer and the first secretary of the board of visitors. Mr. Harris died in 1920.

Henry Clay Harris was a member of the House of Delegates from 1873 to 1875, and involved in the Republican Party from the local to the national level. Born early in the 1840s probably in Buckingham County and perhaps into slavery, Harris went to Philadelphia and Ohio to be educated. When he returned to Virginia in 1867 he began participating in local politics. In November 1873, he won election to a two-year term for a seat in the House of Delegates from Halifax County. During his tenure in the House of Delegates and after he lost his election for the Senate of Virginia in 1875, Harris fought against attempts to restrict African Americans’ right to vote. With his nomination in 1899 to the House of Delegates by Republicans in Halifax, Harris became one of the last African Americans a major party is known to have nominated for the General Assembly until after World War II. He lost the election. The date and place of his death and burial are not known. The last known appearance of Harris is 1905 in the Halifax County records.

Henry C. Hill, member of the House of Delegates (1873–1875), was born free about 1815 in Amelia County. He married Ann Jane Haskins about 1850. The two had twelve children, at least eight of whom survived to adulthood. In the early 1870s he became active in local politics and a leader among African American Republicans in Amelia County. After an unsuccessful 1871 candidate for the Republican nomination for the House of Delegates, in 1873 he won a two-year term representing Amelia County. Not particularly active during his legislative service, he did not run for a second term. Between 1870 and 1895, he served several terms as a justice of the peace and was also a trustee of his Baptist church. He bought and sold land in the 1880s and 1890s. Hill died on September 7, 1905, most likely in Amelia County, and is probably buried in the Bethia Baptist Church cemetery, where some of his children and his wife were later buried.

Charles E. Hodges represented Norfolk County in the House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871. Born in Princess Anne County (later the city of Virginia Beach), he was the son of prosperous free African Americans. His older brother Willis A. Hodges served in the Convention of 1867–1868 and his nephew John Quincy Hodges served with him in the House of Delegates. In 1850 he was swindled out of land and the next year moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he became a Baptist preacher. He returned to Virginia during the Civil War. In 1869 Mr. Hodges won election to the General Assembly, where he voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, supported the Funding Act of 1871, and unsuccessfully opposed segregation in the new statewide public school system. In his later years he served as a Baptist preacher and won election as a justice of the peace in Norfolk County (later the city of Chesapeake). Mr. Hodges died sometime after being counted in the federal census of 1910. (Photo credit: Bells Mill Historical Research and Restoration Society, Inc., Chesapeake, VA.)

John Quincy Hodges was an African American leader in Norfolk and Princess Anne County after the Civil War and member of the House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871. Born in what later became Brooklyn, New York, he was the son of a free African American father and an English mother. Name for former president John Quincy Adams, little is known about his early life, but he served with the United States Army during the Civil War and was present at the surrender of Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina. His uncle Willis A. Hodges, served in the Convention of 1867–1868, while another uncle, Charles E. Hodges, served with him in the House of Delegates. Using their popularity to become well-known too, he won election in 1869 to represent Princess Anne County (later the city of Virginia Beach) in the House of Delegates. Mr. Hodges voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, as well as the Funding Act of 1871. After several run-ins with the law in the 1870s he returned to New York, where he worked as a clerk. Mr. Hodges died sometime after the census enumeration in 1900.

Henry Johnson was born a slave in Amelia County in 1842. His parents were David and Louisa Johnson. During slavery, he was taught to read by a white man to whom he gave food in exchange for his lessons. After slavery, he continued his informal education at the home of James Ferguson, a Richmond native who was the first African American school teacher in Princess Anne County. Mr. Johnson was a shoemaker and teacher. He purchased land in Princess Anne County shortly after Emancipation. He represented Nottoway and Amelia Counties in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1889 to 1890. He died in 1922.

Benjamin F. Jones represented King William County in the House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871. He was born enslaved on the plantation of Anderson Scott, who may have been his father. Upon his death in 1864 Scott emancipated Jones and his family and divided his property among them. Despite a lack of formal education, Jones managed the farm accounts while he was still enslaved. He was elected in 1869 for a two-year term representing King William County in the House of Delegates. After surviving a challenge to his election, he voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U. S. Constitution. Unusually active for a first-term delegate, he introduced many bills related to such issues as hunting, public works, local health care, the indigent, orphans, gambling, and emigration. In 1871 he voted with the majority, including most of the other African American delegates, for a bill to pay the public debt left over from before the American Civil War (1861–1865). Jones continued to farm in King William County until about 1911, when he last appeared in the personal property tax records. The date of his death is unknown.

James Richard Jones, who is difficult to track in the historical record because of confusion in the documentary record about his name, was a member of the Senate of Virginia and of the House of Delegates. In November 1876 he won election to the vacant seat in the Senate of Virginia from the counties of Mecklenburg and Charlotte to complete the short time remaining in the term to which the late Albert P. Lathrop had been reelected in 1873. He ran for election to the full four-year term in 1877 but lost to a white Conservative. Jones held the presidential appointment as postmaster in the town of Boydton 1880 to 1885. He ran as a Readjuster for his old Senate seat in the autumn of 1881 and was elected. Jones successfully sponsored a bill to repair roads in Charlotte and several other counties. He also introduced two bills to abolish the whipping post and voted for a House bill that became law and terminated that painful and humiliating legacy of slavery. For reasons that are not evident, Jones resigned from his Senate seat half-way through his term. In November 1885 Jones defeated Democrat Charles L. Finch to win a two-year term in the House of Delegates to represent Mecklenburg County. He did not win the Republican nomination in 1887, and in December 1888, Jones joined the Capitol Police force in Washington, D.C. The date and place of his death are not recorded.

Peter K. Jones served four terms in the House of Delegates and also sat in the constitutional Convention of 1867–1868. Born free in Petersburg about 1834, he first acquired property in 1857. Politically active after war, he urged African Americans to become self-sufficient and advocated for suffrage and unity. He moved to Greensville County about 1867, and that same year he won a seat at the convention called to write a new state constitution. A member of the convention's radical faction, Mr. Jones voted in favor of granting the vote to African American men and against segregating public schools. He represented Greensville County in the General Assembly from 1869 to 1877, working tirelessly to protect the rights of African Americans. Mr. Jones moved to Washington, D.C., and continued to support African American interests and the Republican Party. He died there in 1895.

Robert G. W. Jones, member of the House of Delegates (1869–1871), was reportedly born free in Henrico County in 1826 but lived most of his life in Charles City County. On July 6, 1869, he easily defeated a Confederate veteran to win election to the House of Delegates representing Charles City County. He voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, as Congress required before it seated senators and representatives from the state. He considered running for reelection in 1871, but a new district had been created and he was shut out of the race. At various times Jones owned property in the county and identified himself as a farmer in census records. He served as one of the trustees of the Union Baptist Church formed during the American Civil War (1861–1865). Winning election as a justice of the peace for the county’s Harrison district in 1883, 1885, 1887, and 1889, he also served as acting coroner on at least one occasion. Jones died on an unrecorded date between August 19, 1899, when representatives of the Lincoln National Building and Loan Association filed suit against him, and March 15, 1900, when an administrator was appointed to oversee his estate.

Rufus Sibb Jones, a member of the House of Delegates (1871–1875), was born about 1834 in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. His family moved to Pittsburgh by 1850, where he was apprenticed to a wigmaker. He attended a school affiliated with an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. In the 1860 U.S. Census he reported his occupation as hair worker and owning $1,000 in personal property. Drafted into the United States Colored Troops during the American Civil War (1861-1865), he became a regimental clerk before mustering out as a sergeant in November 1865. Moving to Virginia after the war, in 1869 Jones worked as a postmaster of Newport News, in Warwick County, and briefly taught in a Freedmen’s Bureau School. He won election in 1871 to a two-year term in the House of Delegates representing the counties of Elizabeth City and Warwick. He was reelected in 1873 but lost a third term in 1875 as well as a bid to the Senate of Virginia in 1877. A practicing attorney, he also served as a justice of the peace, a customs inspector, and a deputy sheriff. He died on July 17, 1897, and is buried at Hampton National Cemetery.

William H. Jordan, member of the House of Delegates (1885–1887), was born probably into slavery in Petersburg, the son of a carpenter or builder. He studied law and in 1887 was permitted to practice in the Petersburg court. By 1888 he may have been the owner or manager of a dry goods and merchandise partnership. He became active in politics and was a staunch follower of fellow Petersburg native William Mahone, who founded the bi-racial Readjuster Party. In 1885 Mahone was influential in Jordan’s contentious Readjuster nomination for and election to a two-year term in representing Petersburg in the House of Delegates. During his term he introduced a bill to incorporate the Colored Agricultural and Industrial Association of Virginia, of which he was an original member of the board of directors and its general manager. In the 1888 congressional election he campaigned against John Mercer Langston, an African American Republican, and for Richard Watson Arnold, the white Republican whom Mahone endorsed. Jordan appears to have left Petersburg after 1889 and possibly worked in the north as a lawyer and railway mail clerk.

Alexander G. Lee, believed to have been born enslaved, of mixed race ancestry, in Portsmouth in the 1830s or early 1840s was a member of the House of Delegates (1877–1879). He lived in Hampton shortly after the conclusion of the American Civil War (1861–1865), married, and worked as an oysterman, laborer, and boatman. In 1873 he ran unsuccessfully for the House of Delegates. Lee ran again in 1877 and won a two-year term representing the counties of Elizabeth City and Warwick. He unsuccessfully tried to pass a resolution to instruct the judge of Elizabeth City County to select jurors regardless of race. After his single term Lee stayed active in local politics. He obtained a federal patronage appointment as a lighthouse keeper, a position he kept until the mid-1880s. He ran again for the House of Delegates in 1887, was defeated, and spent the rest of his life working for the army’s corps of engineers at Fort Monroe. He died, most likely in Hampton, by October 10, 1901.

Neverson Lewis served in the House of Delegates from 1879 to 1882 representing the district that included Chesterfield and Powhatan counties and the city of Manchester. Lewis was born, likely into slavery, in Powhatan County, and lived and farmed there his entire life. In 1879 he won election to the House of Delegates as a Republican Readjuster, meaning that he wanted to adjust the repayment of the old antebellum debt to reduce the amount of principal and the rate of interest in order to save money and increase appropriations for the public schools. Lewis voted to pass the 1880 bill to refinance the debt as Readjusters desired, but the governor vetoed the bill and the Senate failed to override it. Lewis died in 1918 in Powhatan County.

James F. Lipscomb, a farmer and merchant, was born free in Cumberland County in 1830 to a family whose freedom was first granted in 1818. Although he was born in poverty, he learned to read and write and rose by his own efforts from the position of a hack driver in Richmond to the owner of a canal boat on the James River, and finally to the ownership of three farms in Cumberland totaling 510 acres. He built a 12-room house and eight smaller dwellings, which he rented out to his farm tenants. After ending his eight-year career in the General Assembly, Mr. Lipscomb opened a general country store, which was later operated by his grandson. He represented Cumberland County in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1869 to 1877. Mr. Lipscomb died in 1893.

Family document: Nathaniel Harrison and Frankey Miles of Amelia County, VA (Word doc)

Gallery of family documents »

William P. Lucas, member of the House of Delegates (1873–1875), was born into slavery about 1843 in Prince William County. Prepared by his mother’s enslaver to be a house servant, he was taught the alphabet. When the American Civil War (1861–1865) ended, he lived in Orange County, where he had been in service to a Confederate surgeon who operated a hospital. Lucas attended a Freedmen’s Bureau school in the county and became a teacher. He became involved in Republican Party politics and won election in 1873 to a two-year term in the House of Delegates representing Louisa County. Lucas married three times; his first marriage ended in divorce and his second upon the death of his wife, a teacher. He had seven children who lived to adulthood. In 1875 he helped arrange and attended a convention of about 100 African American delegates that met to address economic and political discrimination in Virginia. Lucas purchased a farm in 1874 and in 1881 worked as a postal clerk for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. He died in Louisa County on May 30, 1887.

John Walter Boyd Matthews, member of the House of Delegates (1871–1873), was born free in 1840 in Petersburg. His mother named him after the white planter who bequeathed land and enslaved workers to her and was her father. During the American Civil War (1861-1865) he worked as a barber and in May 1870 he had a job in the city’s customs house. In 1871 he won election to a two-year term in the House of Delegates representing Petersburg. Active in the legislature, Matthews introduced bills, made motions, and spoke more than most Black delegates. Aggressive, if not successful, his failed propositions included abolishing chain gangs for prisoners, raising taxes on alcoholic beverages, and pushing for laws to enforce the state constitution that guaranteed equal rights to all citizens. Matthews was a founding officer of the Petersburg Grant and Wilson Club and served as deputy collector at the City Point customs house. In 1875 he attended a state convention in Richmond that addressed the political and economic discrimination faced by African Americans in Virginia. Mathews died of a stroke at his home in Petersburg on July 11, 1879.

John B. Miller Jr., member of the House of Delegates (1869–1871), was born free in the early 1840s, probably in Henrico County, the son of a cooper and his wife. By 1860 he worked as a barber and owned property deeded to him by his father. In May 1867 he likely lived in Richmond and was named to the interracial jury pool of the United States Circuit Court which, had it been held, would have tried former Confederate president Jefferson Davis. In July 1869 Miller won election to a two-year term in the House of Delegates representing Goochland County. Miller voted to ratify the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which Congress required before it seated senators and representatives from Virginia. He attempted without success to have the House invite African American ministers to open sessions with prayers. He introduced unsuccessful bills addressing fair work measures and racial discrimination. After his legislative career, Miller worked again as a barber, but he and his wife faced financial difficulties, and in 1875 he was charged, and acquitted, with financial fraud. The date and place of his death are unknown, although a February 1896 newspaper article on members of the 1867 interracial jury described him as being deceased.