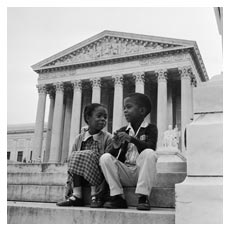

Children sit in front of the Supreme Court, which is hearing arguments about the integration of Little Rock Schools. (Copyright Bettmann/Corbis / AP Images)

Original caption: 12/21/1956-Montgomery, AL- Mrs. Rosa Parks, 43, is shown smiling as she walks on the street here, December 21. (Copyright Bettmann/Corbis / AP Images)

On May 17, 1954, the U. S. Supreme Court held in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), that segregated public schools was unconstitutional. Prior to the Court's decision, African American students in Virginia and across the South were educated in a dual school system, one Black and one white, in abysmal school conditions. The curricula, textbooks, equipment, and school buildings were substandard. African American schools were without gymnasiums, restrooms, cafeterias, lockers, or auditoriums with fixed seating, and students were issued textbooks that were in utter disrepair and discarded by white schools.

In an act of defiance to the landmark Supreme Court decision, Virginia, followed by other Southern states, enacted numerous laws designed to deliberately nullify, obfuscate and delay the ruling and to minimize desegregation wherever it occurred. Virginia embarked upon a public policy of "Massive Resistance" to public school desegregation, which earned the Commonwealth the dubious distinction of depriving thousands of African Americans and white students of an education. In fact, all levels of government demonstrated intense resistance to compliance with the Brown decision and Virginia exhausted every possible means to avoid desegregation. The resistance lasted 10 years. Public schools were first closed in Warren County, and then in Charlottesville, Norfolk, and Prince Edward County. In Arlington, state public education funds were rescinded because the county's public schools did not remain segregated. When public schools were eventually re-opened in some areas of the Commonwealth, African American students, and there were very few, attending white schools were harassed, threatened, isolated, humiliated, and treated with contempt.

In Prince Edward County, public schools remained closed for five years until the Supreme Court ordered the re-opening of the county's public schools in 1964. The General Assembly responded to the 1964 U. S. Supreme Court decision in Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County by repealing the laws it had enacted to protect segregated schools and by dismantling the legislative architecture of Massive Resistance.

After the formal end of Virginia's Massive Resistance, desegregation cases continued to be heard in federal courts until 1984, and the last case was finally dismissed in 2001.

Since 2009, we have observed what appears to be the providential convergence of the anniversaries of several historic events and milestones in Virginia and United States history—the Bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln, the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War, the Sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Bicentennial of the American War of 1812, the Centennial of Woodrow Wilson's Presidency, the 50th anniversary of Massive Resistance, and the 55th anniversary of the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. These commemorations represent the many common threads that are inextricably woven throughout Virginia's history and the impact of history on the African American people. Therefore, the nexus between these historic events cannot be considered through a myopic lens; instead, we must be willing to be guided by the evidence and the story of a people who tapped into an inner courage and strength that has sustained them for centuries of injustice, indignities, and discrimination to right social inequities and injustice, claim their inalienable rights, and make the future better for generations.

The Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Commission and the Brown v. Board of Education Scholarship Committee have established a Special Subcommittee on the Public School Closings in Virginia (Massive Resistance) to commemorate and educate citizens concerning this era in our State's history and the significance of the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision in order that we might avoid the repetition of history. The Special Subcommittee consists of legislative and citizen members of the King Commission and the Brown Committee, and representatives of the legal, business and corporate communities, the state and federal court systems, professional education organizations, public and higher education officials, educators, relevant state agencies and local governing bodies, community organizations, recent Brown scholars, and localities in which public schools were closed to avoid desegregation. The Commission and Committee are giving particular emphasis to informing current students of the State's history to promote greater appreciation and understanding of the sacrifices of a heroic generation who overcame tremendous obstacles to afford them the rights and privileges enjoyed today.

The Special Subcommittee has held Town Hall meetings in each locality in which public schools were closed to facilitate public discussion and dialogue among citizens concerning the history of Massive Resistance, its impact and legacy in their respective localities and the Commonwealth, and ways to promote reconciliation and a common vision for the future.

The Commission desires that the deliberate period of statewide reflection and contemplation of this period in Virginia's history will compel all citizens to strive individually and collectively to fulfill of Dr. King's vision of the "Beloved Community"—a society in which the human dignity and worth of all people is affirmed and where each person is "judged by the content of his character and not by the color of his skin."

A signature project commemorating the closing of public schools in Virginia, the "Massive Resistance Oral History Project (MROHP)," is a Commission collaboration with the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of African American Studies. (See Massive Resistance Oral History Project)